We are hurtling towards a surveillance state’: the rise of facial recognition technology

It can pick out shoplifters, international criminals and lost children in seconds. But as the cameras proliferate, who’s watching the watchers?

Gordon’s wine bar is reached through a discreet side-door, a few paces from the slipstream of London theatregoers and suited professionals powering towards their evening train. A steep staircase plunges visitors into a dimly lit cavern, lined with dusty champagne bottles and faded newspaper clippings, which appears to have had only minor refurbishment since it opened in 1890. “If Miss Havisham was in the licensing trade,” an Evening Standard review once suggested, “this could have been the result.”

The bar’s Dickensian gloom is a selling point for people embarking on affairs, and actors or politicians wanting a quiet drink – but also for pickpockets. When Simon Gordon took over the family business in the early 2000s, he would spend hours scrutinising the faces of the people who haunted his CCTV footage.

“There was one guy who I almost felt I knew,” he says. “He used to come down here the whole time and steal.” The man vanished for a six-month stretch, but then reappeared, chubbier, apparently after a stint in jail. When two of Gordon’s friends visited the bar for lunch and both had their wallets pinched in his presence, he decided to take matters into his own hands. “The police did nothing about it,” he says. “It really annoyed me.”

Gordon is in his early 60s, with sandy hair and a glowing tan that hints at regular visits to Italian vineyards. He makes an unlikely tech entrepreneur, but his frustration spurred him to launch Facewatch, a fast-track crime-reporting platform that allows clients (shops, hotels, casinos) to upload an incident report and CCTV clips to the police. Two years ago, when facial recognition technology was becoming widely available, the business pivoted from simply reporting into active crime deterrence. Nick Fisher, a former retail executive, was appointed Facewatch CEO; Gordon is its chairman.

Gordon installed a £3,000 camera system at the entrance to the bar and, using off-the-shelf software to carry out facial recognition analysis, began collating a private watchlist of people he had observed stealing, being aggressive or causing damage. Almost overnight, the pickpockets vanished, possibly put off by a warning at the entrance that the cameras are in use.

The company has since rolled out the service to at least 15 “household name retailers”, which can upload photographs of people suspected of shoplifting, or other crimes, to a centralised rogues’ gallery in the cloud. Facewatch provides subscribers with a high-resolution camera that can be mounted at the entrance to their premises, capturing the faces of everyone who walks in. These images are sent to a computer, which extracts biometric information and compares it to faces in the database. If there’s a close match, the shop or bar manager receives a ping on their mobile phone, allowing them to monitor the target or ask them to leave; otherwise, the biometric data is discarded. It’s a process that takes seconds.

Facewatch HQ is around the corner from Gordon’s, brightly lit and furnished like a tech company. Fisher invites me to approach a fisheye CCTV camera mounted at face height on the office wall; he reassures me that I won’t be entered on to the watchlist. The camera captures a thumbnail photo of my face, which is beamed to an “edge box” (a sophisticated computer) and converted into a string of numbers. My biometric data is then compared with that of the faces on the watchlist. I am not a match: “It has no history of you,” Fisher explains. However, when he walks in front of the camera, his phone pings almost instantly, as his face is matched to a seven-year-old photo that he has saved in a test watchlist.

“If you’re not a subject of interest, we don’t store any images,” Fisher says. “The argument that you walk in front of a facial recognition camera, and it gets stored and you get tracked is just.” He pauses. “It depends who’s using it.”

While researching theft prevention, Fisher consulted a career criminal from Leeds who told him that, for people in his line of work, “the holy grail is, don’t get recognised”. This, he says, makes Facewatch the ultimate deterrent. He tells me he has signed a deal with a major UK supermarket chain (he won’t reveal which) and is set to roll out the system across their stores this autumn. On a conservative estimate, Fisher says, Facewatch will have 5,000 cameras across the UK by 2022.

The company also has a contract with the Brazilian police, who have used the platform in Rio de Janeiro.

“We caught the number two on Interpol’s most-wanted South America list, a drug baron,”

says Fisher, who adds the system also led to the capture of a male murderer who had been on the run for several years, spotted dressed as a woman at the Rio carnival. I ask him whether people are right to be concerned about the potential of facial recognition to erode personal privacy.

“My view is that, if you’ve got something to be worried about, you should probably be worried,” he says. “If it’s used proportionately and responsibly, it’s probably one of the safest technologies today.

Unsurprisingly, not everyone sees things this way. In the past year, as the use of facial recognition technology by police and private companies has increased, the debate has intensified over the threat it could pose to personal privacy and marginalised groups.

The cameras have been tested by the Metropolitan police at Notting Hill carnival, a Remembrance Sunday commemoration, and at the Westfield shopping centre in Stratford, east London. This summer, the London mayor, Sadiq Khan, wrote to the owners of a private development in King’s Cross, demanding more information after it emerged that facial recognition had been deployed there for unknown purposes.

In May, Ed Bridges, a public affairs manager at Cardiff University, launched a landmark legal case against South Wales police. He had noticed facial recognition cameras in use while Christmas shopping in Cardiff city centre in 2018. Bridges was troubled by the intrusion. “It was only when I got close enough to the van to read the words ‘facial recognition technology’ that I realised what it was, by which time I would’ve already had my data captured and processed,” he says. When he noticed the cameras again a few months later, at a peaceful protest in Cardiff against the arms trade, he was even more concerned: it felt like an infringement of privacy, designed to deter people from protesting. South Wales police have been using the technology since 2017, often at major sporting and music events, to spot people suspected of crimes, and other “persons of interest”. Their most recent deployment, in September, was at the Elvis Festival in Porthcawl.

“I didn’t wake up one morning and think, ‘I want to take my local police to court’,” Bridges says. “The objection I had was over the way they were using the technology. The police in this country police by consent. This undermines trust in them.”

During a three-day hearing, lawyers for Bridge, supported by the human rights group Liberty, alleged the surveillance operation breached data protection and equality laws. But last month, Cardiff’s high court ruled that the trial, backed by £2m from the Home Office, had been lawful. Bridges is appealing, but South Wales police are pushing forward with a new trial of a facial recognition app on officers’ mobile phones. The force says it will enable officers to confirm the identity of a suspect “almost instantaneously, even if that suspect provides false or misleading details, thus securing their quick arrest”.

The Metropolitan police have also been the subject of a judicial review by the privacy group Big Brother Watch and the Green peer Jenny Jones, who discovered that her own picture was held on a police database of “domestic extremists”.

In contrast with DNA and fingerprint data, which normally have to be destroyed within a certain time period if individuals are arrested or charged but not convicted, there are no specific rules in the UK on the retention of facial images. The Police National Database has snowballed to contain about 20m faces, of which a large proportion have never been charged or convicted of an offence. Unlike DNA and fingerprints, this data can also be acquired without a person’s knowledge or consent.

“I think there are really big legal questions,” says Silkie Carlo, director of Big Brother Watch. “The notion of doing biometric identity checks on millions of people to identify a handful of suspects is completely unprecedented. There is no legal basis to do that. It takes us hurtling down the road towards a much more expansive surveillance state.”

Some countries have embraced the potential of facial recognition. In China, which has about 200m surveillance cameras, it has become a major element of the Xue Liang (Sharp Eyes) programme, which ranks the trustworthiness of citizens and penalises or credits them accordingly. Cameras and checkpoints have been rolled out most intensively in the north-western Xinjiang province, where the Uighur people, a Muslim and minority ethnic group, account for nearly half the population. Face scanners at the entrances of shopping malls, mosques and at traffic crossings allow the government to cross-reference with photos on ID cards to track and control the movement of citizens and their access to phone and bank services.

At the other end of the spectrum, San Francisco became the first major US city to ban police and other agencies from using the technology in May this year, with supervisor Aaron Peskin saying: “We can have good policing without being a police state.”

Meanwhile, the UK government has faced harsh criticism from its own biometrics commissioner, Prof Paul Wiles, who said the technology is being rolled out in a “chaotic” fashion in the absence of any clear laws. Brexit has dominated the political agenda for the past three years; while politicians have looked the other way, more and more cameras are being allowed to look at us.

Facial recognition is not a new crime-fighting tool. In 1998, a system called FaceIt, comprising a handful of CCTV cameras linked to a computer, was rolled out to great fanfare by police in the east London borough of Newham. At one stage, it was credited with a 40% drop in crime. But these early systems only worked reliably in the lab. In 2002, a Guardian reporter tried in vain to get spotted by FaceIt after police agreed to add him to their watchlist. He compared the system to a fake burglar alarm on the front of a house: it cuts crime because people believe it works, not because it does.

However, in the past three years, the performance of facial recognition has stepped up dramatically. Independent tests by the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (Nist) found the failure rate for finding a target picture in a database of 12m faces had dropped from 5% in 2010 to 0.1% this year.

The rapid acceleration is thanks, in part, to the goldmine of face images that have been uploaded to Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn and captioned news articles in the past decade. At one time, scientists would create bespoke databases by laboriously photographing hundreds of volunteers at different angles, in different lighting conditions. By 2016, Microsoft had published a dataset, MS Celeb, with 10m face images of 100,000 people harvested from search engines – they included celebrities, broadcasters, business people and anyone with multiple tagged pictures that had been uploaded under a Creative Commons licence, allowing them to be used for research. The dataset was quietly deleted in June, after it emerged that it may have aided the development of software used by the Chinese state to control its Uighur population.

In parallel, hardware companies have developed a new generation of powerful processing chips, called Graphics Processing Units (GPUs), uniquely adapted to crunch through a colossal number of calculations every second. The combination of big data and GPUs paved the way for an entirely new approach to facial recognition, called deep learning, which is powering a wider AI revolution.

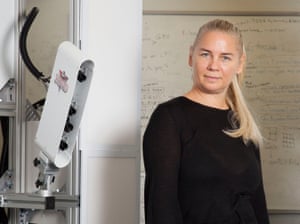

“The performance is just incredible,” says Maja Pantic, research director at Samsung AI Centre, Cambridge, and a pioneer in computer vision. “Deep [learning] solved some of the long-standing problems in object recognition, including face recognition.”

Recognising faces is something like a game of snap – only with millions of cards in play rather than the standard deck of 52. As a human, that skill feels intuitive, but it turns out that our brains perform this task in a surprisingly abstract and mathematical way, which computers are only now learning to emulate. The crux of the problem is this: if you’re only allowed to make a limited number of measurements of a face – 100, say – what do you choose to measure? Which facial landmarks differ most between people, and therefore give you the best shot at distinguishing faces?

A deep-learning program (sometimes referred to more ominously as an “agent”) solves this problem through trial and error. The first step is to give it a training data set, comprising pairs of faces that it tries to match. The program starts out by making random measurements (for example, the distance from ear to ear); its guesses will initially be little better than chance. But at each attempt, it gets feedback on whether it was right or wrong, meaning that over millions of iterations it figures out which facial measurements are the most useful. Once a program has worked out how to distil faces into a string of numbers, the algorithm is packaged up as software that can be sent out into the world, to look at faces it has never seen before.

The performance of facial recognition software varies significantly, but the most effective algorithms available, such as Microsoft’s, or NEC’s NeoFace, very rarely fail to match faces using a high-quality photograph. There is far less information, though, about the performance of these algorithms using images from CCTV cameras, which don’t always give a clear view.

Recent trials reveal some of technology’s real-world shortcomings. When South Wales police tried out their NeoFace system for 55 hours, 2,900 potential matches were flagged, of which 2,755 were false positives and just 18 led to arrests (the number charged was not disclosed). One woman on the watchlist was “spotted” 10 times – none of the sightings turned out to be of her. This led to claims that the software is woefully inaccurate; in fact, police had set the threshold for a match at 60%, meaning that faces do not have to be rated as that similar to be flagged up. This minimises the chance of a person of interest slipping through the net, but also makes a lot of false positives inevitable.

In general, Pantic says, the public overestimates the capabilities of facial recognition. In the absence of concrete details about the purpose of the surveillance in London’s King’s Cross this summer, newspapers speculated that the cameras could be tracking shoppers and storing their biometric data. Pantic dismisses this suggestion as “ridiculous”. Her own team has developed, as far as she is aware, the world’s leading algorithm for learning new faces, and it can only store the information from about 50 faces before it slows down and stops working. “It’s huge work,” she says. “People don’t understand how the technology works, and start spreading fear for no reason.”

This week, the Met police revealed that seven images of suspects and missing people had been supplied to the King’s Cross estate “to assist in the prevention of crime”, after earlier denying any involvement. Writing to the London Assembly, the deputy London mayor, Sophie Linden, said she “wanted to pass on the [Metropolitan police service’s] apology” for failing to previously disclose that the scheme existed, and announced that similar local image-sharing agreements were now banned. The police did not disclose whether any related arrests took place.

Like many of those working at the sharp end of AI, Pantic believes the controversy is “super overblown”. After all, she suggests, how seriously can we take people’s concerns when they willingly upload millions of pictures to Facebook and allow their mobile phone to track their location? “The real problem is the phones,” she says – a surprising statement from the head of Samsung’s AI lab. “You are constantly pushed to have location services on. [Tech companies] know where you are, who you are with, what you ate, what you spent, wherever you are on the Earth.”

Concerns have been raised that facial recognition has a diversity problem, after widely cited research by MIT and Stanford University found that software supplied by three companies misassigned gender in 21% to 35% of cases for darker-skinned women, compared with just 1% for light-skinned men. However, based on the top 20 algorithms, Nist found that there is an average difference of just 0.3% in accuracy between performance for men, women, light- and dark-skinned faces. Even so, says Carlo of Big Brother Watch, the technology’s impact could still be discriminatory because of where it is deployed and whose biometric data ends up on databases. It’s troubling, she says, that for two years, Notting Hill carnival, the country’s largest celebration of Caribbean and black British culture, was seen as an “acceptable testing ground” for the technology.

I ask Fisher about the risk of racial profiling: the charge that some groups may be more likely to fall under suspicion, say, when a shop owner is faced with ambiguous security footage. He dismisses the concern. Facewatch clients are required to record the justification for their decision to upload a picture on to the watchlist and, in a worst-case scenario, he argues, a blameless individual might be approached by a shopkeeper, not thrown into jail.

“You’re talking about human prejudices, you can’t blame the technology for that,” he says.

After our interview, I email several times to ask for a demographic breakdown of the people on the watchlist, which Fisher had offered to provide; Facewatch declines.

Bhuwan Ribhu grew up in Delhi, in a small apartment with his parents, his sister Asmita, and many children who had been rescued from slavery and exploitation. Like Gordon, Ribhu followed his parents into the family business – in his case, tracking down India’s missing children, who have been enticed, forcibly taken or sold by their parents to traffickers, and end up working in illegal factories, quarries, farms and brothels. His father is the Nobel Peace laureate Kailash Satyarthi, who founded the campaign Bachpan Bachao Andolan (Save Childhood Movement) in 1980, after realising that he could not accommodate all of the children being rescued in the family home.

The scale of the challenge is almost incomprehensible: 63,407 child kidnappings were reported to Indian police in 2016, according to the National Crime Records Bureau. Many children later resurface, but the sheer numbers involved mean it can take months or years to reunite them with their families. “About 300,000 children have gone missing over the last five or six years, and 100,000 children are housed in various childcare institutions,” says Ribhu. “For many of those, there is a parent out there looking for their child. But it is impossible to manually go through them all.”

He describes the case of Sonu, a boy from India’s rural Bihar region, 1,000km from Delhi. When Sonu was 13, his parents entrusted him to a factory owner who promised him a better life and money. But they quickly lost track of their son’s whereabouts and began to fear for his safety. Eventually they contacted Bachpan Bachao Andolan for help. Sonu was tracked down after about two years, hundreds of miles from home. “We found the child after sending out his photo to about 1,700 childcare institutions across India,” Ribhu says. “One of them called us back and said they might have the child. People went and physically verified it. We were looking for one child in a country of 1.3 billion.”

Ribhu had read a newspaper article about the use of facial recognition to identify terrorists at airports and realised it could help. India has created two centralised databases in recent years: one containing photos of missing children, and the other containing photos of children housed in childcare institutions. In April last year, a trial was launched to see whether facial recognition software could be used to match the identities of missing and found children in the Delhi region. The trial was quickly hailed a success, with international news reports suggesting that “nearly 3,000 children” had been identified within four days. This was an exaggeration: the 3,000 figure refers to potential matches flagged by the software, not verified identifications, and it proves difficult to find out how many children have been returned to parents. (The Ministry of Women and Child Development did not respond to questions.) But Ribhu says that, since being rolled out nationally in April, there have been 10,561 possible matches and the charity has “unofficial knowledge” of more than 800 of these having been verified. “It has already started making a difference,” he says. “For the parents whose child has been returned because of these efforts, for the parents whose child has not gone missing because the traffickers are in jail. We are using all the technological solutions available.”

Watching footage of Sonu being reunited with his parents in a recent documentary, The Price Of Free, it is hard to argue against the deployment of a technology that could have ended his ordeal more quickly. Nonetheless, some privacy activists say such successes are used to distract from a more open-ended surveillance agenda. In July, India’s Home Ministry put out a tender for a new Automated Facial Recognition System (AFRS) to help use real-time CCTV footage to identify missing children – but also criminals and others, by comparing the footage with a “watchlist” curated from police databases or other sources.

Real-time facial recognition, if combined with the world’s largest biometric database (known as Aadhaar), could create the “perfect Orwellian state”, according to Vidushi Marda, a legal researcher at the human rights campaign group Article 19. About 90% of the Indian population are enrolled in Aadhaar, which allocates people a 12-digit ID number to access government services, and requires the submission of a photograph, fingerprints and iris scans. Police do not currently have access to Aadhaar records, but some fear that this could change.

“If you say we’re finding missing children with a technology, it’s very difficult for anyone to say, ‘Don’t do it’,” Marda says. “But I think just rolling it out now is more dangerous than good.”

Debates about civil liberties are often dictated by instinct: ultimately, how much do you trust law enforcement and private companies to do the right thing? When searching for common ground, I notice that both sides frequently reference China as an undesirable endpoint. Fisher thinks that the recent disquiet about facial recognition stems from the paranoia people feel after reading about its deployment there. “They’ve created digital prisons using facial recognition technology. You can’t use your credit card, you can’t get a taxi, you can’t get a bus, your mobile phone stops working,” he says. “But that’s China. We’re not China.”

Groups such as Liberty and Big Brother Watch say the opposite: since facial recognition, by definition, requires every face in a crowd to be scanned to identify a single suspect, it will turn any country that adopts it into a police state. “China has made a strategic choice that these technologies will absolutely intrude on people’s liberty,” says biometrics commissioner Paul Wiles. “The decisions we make will decide the future of our social and political world.”

For now, it seems that the question of whether facial recognition will make us safer, or represents a new kind of unsafe, is being left largely to chance. “You can’t leave [this question] to people who want to use the technology,” Wiles says. “It shouldn’t be the owners of the space around King’s Cross, it shouldn’t be Facewatch, it shouldn’t be the police or ministers alone – it should be parliament.”

After leaving the Facewatch office, I walk along the terrace of Gordon’s, where a couple of lunchtime customers are enjoying a bottle of red in the sunshine, and past the fisheye lens at the entrance to the bar, which I now know is beaming my face to the computer cloud. I think back to a winky promise I’ve read on the Gordon’s website: “Make your way to the cellar to your rickety candlelit table – anonymity is guaranteed!”

Out in the wider world, anonymity is no longer guaranteed. Facial recognition gives police and companies the means of identifying and tracking people of interest, while others are free to go about their business. The real question is: who gets that privilege?

Facewatch

Facewatch